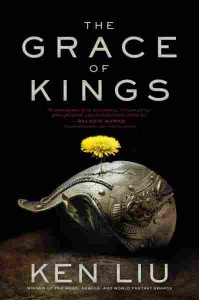

“The Grace of Kings” by Ken Liu

There’s been a lot of anticipation about the release of The Grace of Kings, Ken Liu’s debut novel. If you haven’t heard of Ken Liu, he’s an accomplished writer of short fiction – his story, Paper Menagerie, won the Hugo, the Nebula and the World Fantasy Award. I was very excited to get an advance review copy, and I’m glad to say that it didn’t disappoint.

There’s been a lot of anticipation about the release of The Grace of Kings, Ken Liu’s debut novel. If you haven’t heard of Ken Liu, he’s an accomplished writer of short fiction – his story, Paper Menagerie, won the Hugo, the Nebula and the World Fantasy Award. I was very excited to get an advance review copy, and I’m glad to say that it didn’t disappoint.

Emperor Mapidéré has achieved the seemingly impossible dream unifying of the islands of Dara, but he’s dying, and his empire is buckling under the strain of his autocratic rule. In a time ripe for rebellion, Kuni Garu, a charismatic working-class rogue (the “Dandelion”), and Mata Zyndu, the proud son of a fallen aristrocratic family (the “Chrysanthemum”) are determined to see that dream through. At the brink of victory, though, their fast friendship suddenly turns into deadly enmity, and things aren’t quite so clear cut.

The writing style and narrative structure of The Grace of Kings is fairly unique – it is told simply but perceptively, with myth/folktale qualities. I read somewhere that it’s influenced by Chinese pingshu storytelling, but I know nothing about that. There’s no point of view character, instead we get the whole story from a variety of different points of view as the plot demands, sometimes switching to entirely new characters from across the continent from where our protagonists are. None of the scenes lasts very long, the dialogue is economical and direct (but not so much so as to be unrealistic/humorous like the Belgariad, for example) but still conveys immense subtlety.

I ended up comparing The Grace of Kings to The Lions of Al-Rassan (review here), which I read only a few weeks ago, and it’s not really a fair comparison, but I’ll talk about it since I’m sure it influences my review. Both books are about two larger than life men and the conflict that they are forced into, and both have extraordinary but different styles of prose. In The Lions of Al-Rassan, we’re firmly focused on the characters – Rodrigo Belmonte and Ammar ibn Khairan are truly larger than life, incredible, men through the force of their own personalities, representing the best a human can aim to be. The reader cannot help but love them. In The Grace of Kings, the focus is more on the tale that is being told – Kuni Garu and Mata Zyndu are more a product of their circumstances. Their personalities are very much evident, but much of what they do is because of advice, politics, the intervention of the gods. They are certainly extraordinary heroes within their world, but they still act in accordance with their natures, they don’t try to rise above them.

This makes complete sense if you look at it in terms of Western and Eastern philosophy – the Western tradition focused a lot on improving the self and the role of every individual (The Lions of Al-Rassan is a parallel of Moorish Spain), but Eastern philosophy emphasizes interconnectedness and inevitability (The Grace of Kings is inspired by ancient China). It’s a pretty minor distinction, but it made The Grace of Kings seem grimmer and not have as much heart, although it just comes from using a different storytelling tradition.

Okay, so this book is well-written, but it is also a lot of fun. Ken Liu calls it “silkpunk” – a riff on steampunk that is inspired by East Asian antiquity, and it features some fascinating takes on traditional steampunk technologies – airships, submarines, gliders, and other cool gadgets. There are multiple wars in this book, so there’s plenty of thrilling and often cinematic action. There’s a lot of unexpected humor, and some truly dramatic moments (the one where Mata Zyndu finds his horse, for instance), often aided by the gods.

Speaking of the gods, I loved how they were portrayed. Each of the countries has their own god, and they (of course) swear not to interfere in the affairs of mortals, and manage to sneak a whole bunch of interfering in while keeping to the letter of their agreement. They’re often not any wiser than the mortals, though, and although their motivations can be mysterious, sometimes they are quite petty. I’m familiar with spiteful, squabbling gods from Hindu mythology, and they heightened the mythological feel of the book.

Although the plot of the book was based loosely on the rise of the Han dynasty in ancient China, I appreciated the fact that the world was very different from ancient China. The Islands of Dara are an archipelago, for one, and their customs are not distinctly evocative of any one place (Ken Liu talks about why he decided to do that here). The world seemed organically built based on the geography and the cultural interplay, and that is the best kind of world.

The one thing that I didn’t enjoy about the book was how much of what happened happened because people were greedy and power-hungry. I think this goes back to the same kind of inevitability that I talked about earlier – it almost felt like many of the characters were the same kind of person, and the only reason they acted differently was because of their circumstances. Rebels replaced tyrants and became tyrants themselves, competent men and women let their competency go to their head and ended up destroying everything they’d worked for because they wanted more power. There were exceptions, but even they were tempted. It seemed like a world where ambition was expected, or maybe the story only focused on the ambitious people; I’m not sure – it is a book that’s about empires toppling, after all. I kept wishing for some nice characters, but they all ended up dead. If you’re a fan of A Song of Ice and Fire etc., this may be a feature, not a bug.

I’m uncertain about how I feel about the end of the book. It was a self-contained story, but the way everyone was acting made me uneasy for the future. It does make me excited to read the next book, though – especially because Ken Liu has said that each book will have a different theme, and the next one will focus more on historical misogyny.